Written by Bob Hearn - https://bobhearn.blogspot.fr

I hardly know where to begin with this race report. The Spartathlon has been my training focus for the entire year; I have been totally obsessed with it. I've read maybe 50-60 race reports, all of them I could find. When I ran out of English ones, I ran the others on the Spartathlon website through Google Translate. So, having read some really thorough and excellent reports, I feel like anything I write will just be an echo. But my experience was still my own, and nobody else's, so I will put it down, at least for my own benefit. And hopefully my readers will not have the Spartathlon report fatigue that I do at this point.

But I am afraid that like the race, this report is also of epic length. Everything about this race is just... big. Really big. I mean, you have seriously never seen a race report this long. I literally wrote down everything I can remember; I felt compelled to. I'm not saying this is a good thing; I wrote it for myself, or for completist potential Spartathletes looking for as much insight as they can get into the race. At least, it's different from all the other reports. Feel free to skip to the end. (Spoiler: it went well.) Or, at least down to the actual race, starting with Athens to Corinth. Or for the ultra-concise version, you can read this piece in the Dallas Morning News by my friend Spareribs LaMothe.

But I am afraid that like the race, this report is also of epic length. Everything about this race is just... big. Really big. I mean, you have seriously never seen a race report this long. I literally wrote down everything I can remember; I felt compelled to. I'm not saying this is a good thing; I wrote it for myself, or for completist potential Spartathletes looking for as much insight as they can get into the race. At least, it's different from all the other reports. Feel free to skip to the end. (Spoiler: it went well.) Or, at least down to the actual race, starting with Athens to Corinth. Or for the ultra-concise version, you can read this piece in the Dallas Morning News by my friend Spareribs LaMothe.

The Greatest Footrace on Earth

Well, let's start with this: what is the Spartathlon? By the numbers, it's a 153.4-mile race, from Athens to Sparta, Greece, mostly road, though there is some technical trail as you cross a mountain 100 miles in. What makes this challenging (if that sounds easy!) is the strict time cutoffs. In addition to the overall 36-hour cutoff, each of 74 checkpoints along the way has its own cutoff, and the early ones seem sadistically designed to force you to start too fast. When I first read about the race, a couple of years ago, these stats alone were enough to deter me from serious interest. That's like running Western States sub-24 for the silver buckle, something most don't accomplish, and then continuing that pace for another 50+ miles, just to beat the cutoffs?! Yeah right. Except no, not really. It's not a trail race, and there's far less elevation change. That places it into the realm of the possible. Theoretically.

But. The numbers don't scratch the surface of what this race is about. Why this distance, why this time? Those are not arbitrary. If you're a runner, or even if you're not, you probably know the basics of the history of the marathon race. The Persians invaded Greece in 490 BC, the Greeks defeated them at the Battle of Marathon, and they sent Pheidippides to run back to Athens to deliver the good news. Having done so, he promptly died. Thus, the marathon. Except – it turns out that probably never happened. What did happen, actually documented in Herodotus, based on eyewitness accounts, is this. Before the Battle of Marathon, the Athenians sent Pheidippides from Athens to Sparta, to try to recruit the Spartans to help defend Greece. Herodotus records that "he reached Sparta on the very next day after quitting the city of Athens" – so, within about 36 hours. Is this really possible? In 1982, some RAF officers, led by John Foden, decided to find out. After researching Pheidippides' most likely route, they attempted it themselves, and three of them succeeded within the approximately day-and-a-half time limit. The following year, it became an official race.

The Spartathlon was born. Since then it has become one of the premier ultramarathons in the world, and an event that the Greek people along the course celebrate and honor. It's been said that the Spartathlon should be considered "the greatest footrace on Earth, due to the historical underpinnings of the event, the professionalism of the organisers, and the atmosphere of the race". I will not disagree. OK – I was now hooked.

Getting There

To run the Spartathlon, you first have to qualify. There are a variety of ways to do so, none of them easy; only runners with solid credentials are admitted. Even so, typically only about a third of the 300-odd starters finish within the cutoffs. I qualified with 139.5 miles at the New Year's One Day in San Francisco. Actually, lucky for me, I "auto-qualified": if you beat a qualification standard by 20%, you are automatically in; otherwise, you are in the lottery. This year, that made a big difference. Each country (with a few exceptions) is limited to 25 participants – the race has a very international flavor. We've never had more than 10 before from the U.S. This year, we had 38 qualified applicants, and 23 of them auto-qualified. So if you didn't auto-qualify, you had very little chance of getting in.

Knowing in January that I was in, I mapped out my training year around Spartathlon. I had only one other goal race this year, Umstead 100, in April, which was also Spartathlon training. Besides that, I ran two marathons, six 50Ks, and one 100K (Miwok), but all of them were run as long training runs, fitting into my training plan. Other long runs included the Western States Training Camp, and pacing friends at Western States and the San Francisco 100. My last long run was the Burning Man 50K, which was an absolute blast.

Ultimately I did not quite hit my training mileage goals. I've had two persistent issues, that limited me. First, I tore my left hamstring tendons two years ago, and I still have to be careful with that. Second, I have chronic issues with my right Achilles. Fortunately, as the race approached, I was able to ramp up my mileage without either issue becoming worse. My last five weeks of training were 75, 75, 80, 85, and 90 miles. Many ultrarunners (and especially Spartathletes) run much higher mileage, but this is high for me; my peak training weeks prior to this had been 80 miles. I felt good at the end of this, heading into taper.

Besides mileage, there are a ton of logistics to consider for this race, and nutrition would have to be a huge one, as really it is for any long ultra. Almost every Spartathlon report I've read features some kind of stomach issues. Actually, GI issues are the #1 reason for DNFs in ultramarathons more generally. With the strict time limits at Spartathlon, there is even less room for error. If you get behind on calories, there's likely not going to be time to slow down and rebuild. But here, I was prepared. For the past year, I've trained low-carb high-fat, essentially not eating carbs during training. This sounds counterintuitive for running long – isn't it all about the carbs? But actually, it's an increasingly popular training regimen these days, followed by many of the top runners. The basic idea is that you train your body to burn fat more efficiently. You can only store about 2,000 calories worth of carbs in your muscles and liver, but you carry essentially unlimited fat reserves. Normally you can't burn this fat fast enough, so the typical ultrarunner will try to take in something like 300 calories per hour in a race. This can get challenging after 50 or so miles, especially if it's hot, and more blood is diverted to the skin for cooling. The stomach and gut can't keep up; nausea is common. But since becoming adapted to this training, having experimented in many races, I've discovered I can get by just fine on 75-100 calories per hour, which I can easily get from just drinking a bit of Coke now and then – a totally minimal load on my digestive system. Really this is perfect for the Spartathlon: there are aid stations about every two miles (unheard of for ultras), and all of them have Coke! This training has really taken nutrition off the table for me as an issue in races, which is a huge benefit.

Another factor you have to prepare for is the heat and humidity. The race is held in late September, because that's when Pheidippides ran it. But Greece is typically hot and humid this time of year. Some years it is so bad that two-thirds of the field has already dropped by the 50-mile mark! Living in the SF Bay Area, I did get plenty of hot days to train in this summer. But humidity is another matter; it's unheard of here. That destroys me, and really it was my biggest concern heading into the race. So I followed the same sauna-training protocol used by Badwater runners, that I had done twice before for Western States. I planned to build from half an hour up to an hour in the sauna, drinking a lot of water, and running in place a bit at the end. This time, I added in a few days in the steam room; that was really tough. Fortunately you can get the full benefit of sauna training after only 10 or so sessions; I started this when I began my taper. Even so, this time I found the sauna especially challenging, and I didn't make it up to a full hour. I think I was fighting off a cold towards the end, so I backed off. But the training did pay off in the end.

Yes, it really is that simple. No, I never take any salt. No, I don't cramp. That's a myth.

Now, about pacing. I worked up a detailed plan before leaving for Greece. At a race like this, so long and with strict cutoffs, getting this right is critical. And so many people totally screw it up. I just can't comprehend that. The first thing to note is that though the overall cutoff is 36 hours for 150+ miles, the 50-mile cutoff is 9:30. Uh. What?? You are seemingly forced to go out too fast. I like to run even to negative splits where possible, yes, even in ultras. Here, with the mountain at 100 miles, that's maybe less possible, but with the cutoffs it's just a nonstarter, at least if you're going to be anywhere close to 36 hours. And yet – I read so many race reports where people try to build large cushions on the cutoff even by 50 miles. That seems like a recipe for how to DNF. Now, you don't want to be riding the cutoffs too closely, with no room for error; I tell myself that 9ish at 50 is a good target.

But really pacing has to be driven by the overall time goal, right? What was my goal? Given that historically, two-thirds don't finish, it seems reasonable – especially my first time out – to make finishing my goal. But it's hard not to have higher aspirations as well. Thirty hours seems like a benchmark for a really good race. Only a small handful of Americans have ever done this, and typically that would put you in maybe the top 20, in a highly competitive international field. So, sub-30 would be my dream race. It would be nice to leave the door open for that possibility, while not committing to it so early that I risked starting too fast. "Realistically" I was thinking maybe 32-34, based on all the reports I'd read and performances I'd seen, comparing my ultrasignup stats with other runners'. I put that in quotes because, again, most don't even finish within the 36-hour cutoff, and it seemed presumptuous to think of faster as realistic. It's not just the unprepared and inexperienced that don't finish here. They won't even qualify to make it to the start line. The list of DNFs includes a who's-who of top ultrarunners. This is a race that can chew you up and spit you out, no matter who you are.

But. On paper, this is a race that plays to my strengths as a runner. Though I love trails, I do better on roads, the longer the better. But I also have the trail experience for the mountain, and good quad strength and endurance to take full advantage of the long downhills towards the end. Plus I'm a smart pacer, and I don't have to fret too much about nutrition. So yes, I leave the door open for sub-30. I can see it happening if everything clicks.

So, I sat down to make a detailed pacing plan. I started with two things: first, a gpx file of the course, from the British Spartathlon Facebook page, and second, a spreadsheet incorporating all the checkpoint distances and cutoffs, again from the British page. (They are really organized, and also have great artwork and team shirts.) With much further processing, I produced a detailed elevation profile from the gpx file, better than I had been able to find online. I mapped out the checkpoint locations using the official map on the Spartathlon site, correlating key elevation features to checkpoints, recording them in the spreadsheet, and marking key checkpoints on the elevation profile. I think the exercise itself here was perhaps even more valuable than the product, because it got all the course details firmly into my mind. I had read tons of race reports, but a lot of that had been months prior, and the details had faded. I hemmed and hawed, but decided to go with miles instead of kilometers everywhere. The checkpoints all have signs with tons of information on them, in metric, so I'd be making them less useful, but I had to accept that I just think in miles and minutes / mile.

Now, the pace targets. How to choose those? My strategy, which seemed smart at the time, was this: place two anchors, say 29:30 at the finish for the fastest possible time, and 8:45 at mile 50 for the fastest possible time. (I knew it would be hard to run as slow as 9:00 to 50, given the early energy and excitement.) Those anchors meant being 6:30 ahead of the cutoffs at the finish, and 0:45 ahead at mile 50, Corinth. So I'd have to "speed up" quite a bit after Corinth, in terms of building cushion. (However, the cutoffs are also most aggressive at Corinth; they get much easier later, and are also adjusted for elevation profile.) Then, I just interpolated the cutoff buffer by distance between the anchors, and subtracted from the cutoff to arrive at a goal time per checkpoint. Again, this was for "fastest possible" time. A time Liz would not need to arrive at any crew access points before, and a time I could hopefully keep myself from running faster than too early. I would not hesitate (so I told myself!) to run much slower if it felt like I was pushing it at the fastest paces; the overriding goal was still to finish. As I said, this plan seemed smart at the time, but the race exposed some flaws in my reasoning here.

Overall, though, I think this was the right approach: start with what seems like a best-possible goal, based on all the evidence, and work backwards to get splits, which lead to paces. Others I saw using the reverse approach: figure out per segment, based on the elevation profile, what a reasonable pace seems like for that segment, and then see what that adds up to. My feeling was that what a reasonable pace was on race day, on the actual course, might be very different from what it looked like on paper. I preferred to go based on what the history said.

Actually, having said all this, until a week before the race I was leaning towards a much simpler, but still I think sensible plan: hit Corinth around nine hours, and try to minimize the fade after that. Really, that might have been good enough, though having concrete numbers in front of me showing what it would realistically take for sub-30 was useful and motivating.

Finally, I need to talk about gear. This is a very long race run in possibly dramatically varying conditions. Bad gear selection can shut you down, and it turns out I did have big gear issues; others had worse issues, and DNFed because of them. The good thing is that, with checkpoints about every two miles, and the ability to leave drop bags at any of them, you can really go pretty light. There's no need for a hydration vest. A single 20-oz. handheld almost seems like overkill. However, I went with one, instead of a smaller bottle (or none at all, an actual possibility), so that I'd be able to put ice in the bottle, and squirt myself to keep cool between checkpoints. I also wore a minimal belt, the Ultimate Direction Jurek Essential Waist Pack. (Appropriate, as Scott Jurek is the only American to have ever won Spartathlon, which he did three years in a row, 2006-2008. Only the immortal Yiannis Kouros has run it faster.) I used this to hold my clip-on sunglasses, my runner ID card (which you're required to carry with you), my pace charts, and for a while my headlamp and spare batteries. I struggled with shirt selection, not having really run in humid weather. Others I knew wore a longsleeve compression shirt, but I decided to just go with singlet, plus the Way2Cool arm sleeves that had worked well for me at Western States. Shorts were the Asics Men's Distance Short, which have worked well for me for years, never chafing as long as I use BodyGlide. Well, there's a first time for everything.

Shoes were my real dilemma. My favorite shoe, the Saucony Fastwitch 4, is long discontinued, and I've run out of dregs via eBay. This would be my first major race without them. In the end I settled on the Hoka Clifton 2, not really thrilled about the weight or the fit, but wanting some substantial cushion for a 153-mile road race. If I had it to do over I think I'd go with the Fastwitch 7 (a poor substitute for the 4, but maybe better than any alternative), possibly doubling the insoles and switching to a fresh pair midway. Anyway, suffice to say, if your feet are not seriously abused by the end of this race, you must be really tight with the Shoe Gods. So it's worth thinking over shoe selection carefully, to try to limit the damage to serious abuse, as opposed to DNF.

Rounding out the gear: socks – as always, Injinji lightweight socks. Hat – ZombieRunner desert hat, with a sun flap. This was fine, and also helped with the rain on the second day.

With my fueling plan (drink Coke at every checkpoint), I didn't need to stage gels or any other food in drop bags. I did leave four bags, though. One with headlamp and spare batteries, one with warm clothes for the mountain, one with a change of Hokas for after the mountain, and one for a bit later to drop the warm clothes in. In each I also left spare Injinjis and BodyGlide.

Pre-Race

Coming from California, Liz and I decided to arrive early, to allow extra time for jet lag. Most people arrive Wednesday. Pre-race logistics are Thursday, and the race starts Friday morning, September 25. We got in late Tuesday afternoon, just in time for an easy shake-out run. Yes, it was going to be humid. Glad I did that sauna training.

The race starts at the Acropolis, but the host hotels for pre- and post-race are in a coastal suburb of Athens, Glyfada. Here I should mention how incredible a bargain the Spartathlon is in terms of cost, compared to other races. For 450 euros, you get food and lodging for six nights, the race, with 75 fully stocked aid stations, a post-race celebration lunch with the mayor of Sparta, and a gala awards dinner in Athens. Not to mention the large quantity of swag. I mean, you can't even just stay in Europe for that amount for a week, let alone everything else. The actual cost to the organizers must be much greater than this; they get a lot of additional funding from a foundation. Now, you will be sharing a room in Glyfada. I've heard that they used to put three or four to a room, but now it is two. Because Liz joined me as an official supporter, we had our own room.

Each country is assigned a hotel for its team; the U.S. team was in the Fenix this year, along with Japan and a few other countries. Also the Fenix was where race registration and the pre-race briefing occurred, so we didn't have to walk for that. It is the northernmost of the host hotels, though, and everything in Glyfada you might want to walk to (restaurants, shopping) is a ways south. But the beach is nearby.

I'd been looking forward to meeting the rest of the U.S. team. Of the 24 still on the list – one had dropped form the original 25, after the cutoff for alternate selection – I only knew Traci Falbo (not counting meeting Mike Wardian and Elaine Stypula briefly at Western States). She was one of the stars on the team this year, along with Katy Nagy, Aly Venti, Connie Gardner, and Mike Wardian. The women were all on the U.S. National 24-hour Team this spring at the World Championships in Turin. Nagy took gold and Falbo silver, in dominant performances. On the women's side, it was shaping up to be a contest between our 24-hour women and Szilvia Lubics, the course-record holder and winner for three of the past four years, from Hungary. Wardian is famous for his incredible frequency of high-level racing. To take just one example, recently he decided to go for the 50K treadmill world record. He ran hard and beat it, only to learn that the actual record was slightly faster than he'd thought, so he'd just missed it. So – he turned around and tried again the next day, this time beating the actual record. He has inhuman recuperative powers. He'd said earlier this year he was hoping to win the Spartathlon, so I was very eager to see how he would do.

Over the next couple of days I also met Dave Krupski, Eduardo Enrique Aguilar, and Andrei Nana (finishers of last year's Spartathlon, in Andrei's case the past two), George Myers, Bill Zdon (missed a cutoff last year, back for revenge), Chris Roman, Lara Zoeller (narrowly missed the 24-hour team this year), Amy Costa, Mark Matyazic, Chris Benjamin, Jason Romero (a legally blind runner, running with a single guide the entire way!), and as it turns out my Bay Area neighbors that I had to travel halfway around the world to meet, Ken Zemach and Karl Schnaitter. I heard Eric Clifton, also a running legend, was seen, but I didn't see him. In the end we only had 20 starters, as some of the entrants pulled out late. Still, a record U.S. contingent. There have been years – as recently as 2011 – with no U.S. finishers at all.

It was great to get to know the rest of the team, swap war stories, pick brains about pacing plans. It seemed like almost everyone but me had run Badwater, many of them multiple times. Well, I'd just have to muddle through without that background. Almost everyone seemed to agree with me that it was smart to aim for hitting Corinth in about 9 hours, and hang on from there. (I am excepting here the top women and Wardian, who were in it to place or win.) Surprise, surprise – almost nobody did this.

Wednesday, I waited in the interminable registration line, where we handed in our medical form, if we hadn't already, signed various release forms, and got all our stuff. Bibs (one for front and one for back), chip, participation certificate, shirt, runner ID, supporter badge for Liz, various tickets. Also (very flimsy plastic) drop bags, if we hadn't brought our own, and stickers for the drop bags (nice). It seemed like everyone was using 10-20 drop bags, crazy. It's starting to get real!

|

| Across the street from dinner with Nick. Just a little too odd not to share. |

During the race Liz would learn that (1) Nick knew everybody associated with the race, and (2) he had as long a history of involvement with the race as possible. That first Spartathlon run by the RAF officers, in 1982? Nick had been a high-school student then in Greece, one of I think two kids selected to run stretches of the course with John Foden. Wow! More, Nick and Yiannis were extremely gracious during the entire race, making for an absolutely ideal crewing experience for Liz, and for me as well, as they zipped back and forth between me and Rob. (Yiannis says, "This is the first time I've spent the night with another man's wife and got thanked by the husband!") Rob himself was back for his fourth attempt, having not finished the previous three years. He was another runner who agreed with me that shooting for 9 hours at Corinth made sense... and then didn't quite do this on race day. But we'll get to that.

Thursday went by in a blur. I assembled my drop bags, and dropped them off in the numbered bins. You can literally leave a bag at any of 75 checkpoints. Wow. I read a race report a while back where someone had actually made 75 drop bags – all identical. Then, he would never have to worry about which things he had left where! That's taking things a bit too far in my book.

|

| Crew Nick (left) with John Foden, 1982 |

Thursday went by in a blur. I assembled my drop bags, and dropped them off in the numbered bins. You can literally leave a bag at any of 75 checkpoints. Wow. I read a race report a while back where someone had actually made 75 drop bags – all identical. Then, he would never have to worry about which things he had left where! That's taking things a bit too far in my book.

After this, Andrei distributed the team shirts he'd had made, featuring artwork designed for the team in a contest. We each got one participant shirt and two crew shirts. Thanks, Andrei!

Finally, we had the mandatory race briefing. First in Greek, then French, and English last. No real surprises, but there was a bit of comedy of misunderstanding between some questioners and race director Kostis Papadimitriou, as neither side spoke English as a first language. One thing that is banned here is any sort of "advertising" on our clothes. It was never clear to me what exactly counted as advertising. You're not supposed to show anything but country and running club name. Was a shirt from another race OK? To be sure, I wore my Western States singlet inside-out. And I taped over the logo on my hat (sorry, ZombieRunner!).

After that it was an early dinner in the hotel, and off to bed early. Friday morning, up at 4:15, plenty of time for the 7 am start. The buses left the hotel at 6... in principle. Overall the race is organized incredibly well. But the buses, here and the rest of the weekend, are an area that could definitely use improvement. The drivers don't seem to be aware of any sort of timeline. Eventually an enterprising soul asked when we could get on. Oh, you're ready? OK, get on. Later... oh, you'd actually like to leave now? OK. As someone who typically likes to arrive at a race an hour before the start, this was stressing me out. I needed time for the porta-potty lines, and to do my warmup drills, and for the team photo. It was becoming clear there would not be time, and it would be a scramble just to start on time.

|

| Waiting for the bus |

Indeed, no time for the porta-potty line. Ouch. Well, surely there'd be porta-potties at each aid station, right? (Wrong.) Very abbreviated warmup. And I never found the team photo group, bummer! Also I seemed to have forgotten my chocolate milk, that I chug just before race start, back in my hotel room. After preparing for a huge race for an entire year, messing up the start really rankles. But there was nothing I could do.

The Race, Part I: Athens to Corinth

The start is actually at the Acropolis, in the shadow of the Parthenon. Very cool. It was a mob scene here, people milling to and fro, eventually jockeying for position – if I could figure out which way the start was! I left Liz at the very front, hopefully able to find Nick after the start. Then I found Nick, and pointed him towards her. (Still they had a hard time connecting!)

|

| Ready or not, time to go! |

And we're off!

7 am, and we're off!!! This is it: the biggest running challenge of my life. The sun had not quite risen yet, but it was light enough. Leaving the Acropolis, it was downhill for a while. I'd read about the cobblestones here, how you had to be careful not to turn your ankle, but to me there was nothing that rose to the level of "cobblestone". Also I'd read about how Athens rush-hour traffic was stopped, drivers honking in either support or frustration, never clear which, but I didn't really experience much of this either. I do tend to zone out on my environment in races, focusing on pacing, which often leaves me missing interesting things. Here especially, I really wanted to appreciate my environment. Well, not so much in Athens, apart from the very start, but later in the race, as it became pretty, and we passed through ancient cities.

Right away, I was struggling to run slowly enough, and people were gradually flowing past me. It was cool (though very humid), shaded, downhill. For a short while I was with Amy (Costa) and Mark (Matyazic), then they were gone. I saw Andrei (Nana) go by. After a few miles we turned north to follow the coast, and we had an actual, sizable hill over a couple miles. Not a steep grade at all, easily runnable, but to go as slowly as I needed to I walked some here anyway. If they'd been flowing past before, they were flying past now. I was actually just the barest bit concerned I'd do something stupid and miss one of the very first cutoffs. But after a few checkpoints passed I could stop worrying about that.

Headphones are not allowed at Spartathlon, something I appreciate. I never use them anyway; I much prefer to be connected to my environment (which does sort of contradict what I said above about zoning out; hmm!). Also I appreciate it when those around me are available for conversation instead of tuned-out, though here there are language barriers. However, I usually have some sort of soundtrack playing in my head, whatever my brain has latched on to. This time, for whatever reason, it happened to be a ringtone; ugh! Must be from somebody's phone right before the race. That lasted quite a while, and was eventually replaced with some 80s pop I've now forgotten.

Early in the race I had a lot of nice, if brief, conversations with runners as we ran together before they gradually pulled ahead. Paul Ali from the British team – I was using his spreadsheet. Mimi Anderson, also British. I'd read her report from a couple years ago. She'd been planning to run the race, then turn around and do the return trip as well (as Pheidippides had done)! Unfortunately she hadn't quite finished the outbound trip that year. Was she trying for out-and-back again? Yes! Good luck. And see you later, maybe.

Somewhere in here I caught up to Connie (Gardner), or vice-versa. I told her I was very tempted by the running camp she and Mike Morton are leading in the Cinque Terre region of Italy next spring. I'm trying to talk Liz into it too, but she's not sure about all the hills. Oh, Connie says, she can hike the hills with me, you run ahead with Mike! Then we start talking 24-hour strategy, as my goal is to make the U.S. National 24-Hour Team for 2017. (World Championships have unfortunately gone to every other year, so there will be no 2016 team.) Connie is a veteran of many national 24-hour teams, and a former U.S. record holder at 24-hour. Of course, she's wearing her team USA shirt, like an Olympian; the World Championships are the equivalent of the Olympics for ultrarunners. I would kill for one of those shirts! I came close to making the team this year, with 139.5 miles; 145 would have done it. But I think it will be harder for 2017. There is a lot of interested talent, now crammed into half the space (because no even years). Also the men's qualification standard was bumped from 135 to 140. That doesn't matter much, because they only take the top six for the team, and I think it will likely take 150+ miles to make the cut for 2017. Possibly beyond my capabilities.

Connie is very supportive, and suggests North Coast 24, the U.S. National Championships, says she and/or friends will come out to crew me... unfortunately it's just a couple weeks before Spartathlon, and I kind of have a feeling Spartathlon may be something I have to keep coming back to. Like the Boston Marathon has been (coming up on 12 in a row, but that is kind of getting old now), and later Western States. I can't get in to Western States every year, but since I first ran it in 2012, I have to go back every year one way or another. I paced in 2013, got in again in 2014, and paced again this year. It's a race with a special history and culture. As is Spartathlon. Anyway... Connie also suggests 24 The Hard Way, in Oklahoma, as another great place to qualify for the team. But that's in October, also too close to Spartathlon. I am running Desert Solstice 24 this December; that will be my first shot. She says, you have to go for 150 miles. Yes, I do. It may be beyond me, but even if I miss it, I have a shot at the U.S. 50+ record for 24-hour, 144.623 miles (Ed Ettinghausen). Before long Connie pulls away as well; I won't see her again for a long time.

A few checkpoints later, the sun is up, but it's still not too warm yet. Ken (Zemach) comes up from behind (I think), and we run together for a while, then play leapfrog for a while longer. I finally lose him just before the marathon point, I think. Somewhere in here I was also running with Chris Roman. He has a hip issue, genetic, that's he'll be treating surgically soon, just trying to get through this under the cutoffs today. He seems to be running smart. For quite a while I see Amy just ahead. Eventually I catch up, and we as well play leapfrog for a while.

We are running past refineries now. Reports all complain of the stench, but it doesn't bother me much. Reports also all mention all the wild dogs. There are some, but fewer than I expected, and they don't bother me at all. Throughout the race, I have to keep pinching myself. I am really here. I have read so much, I have a fully detailed model in my head of the whole experience, from pre-race hotels to post-race gala. There is a little bit of cognitive dissonance as sometimes the reality is not quite the same as the model, and ludicrously, I feel that reality is not quite getting it right. It's kind of surreal.

As expected, my left hamstring begins complaining around mile 10. This is the pattern. It ought to quiet down after 30 miles or so. I poke my finger under my butt and feel a tight knot in there that's binding with every stride, and try to massage it loose.

Around 15 miles in, we reach a less industrial part of the course. For a long while now we will be running along the coast, with gorgeous views out over the Saronic Gulf and the island of Salamis. It was here that the Greeks destroyed the Persian fleet in 480 BC, in one of the most significant battles in human history. I think about this as I remember reading about how hot it can get here, with the sun beating down from above, as well as reflecting off the asphalt, the ocean, and the cliff faces to the right. It's not too bad this year... yet.

As we pass through the small coastal towns, children line the route offering high fives. I think they have been let out of school for this. Throughout the course, the locals are all enthusiastic; cries of "Bravo!" fill the air. You get this at Boston too, perhaps the best marathon crowd support anywhere, but here it is different and special. The Greeks feel a lot of pride in this race, and respect that we are honoring their culture and history by participating. This helps give the race an extra substance and depth. It really means something; it's not just running X miles for the sake of running. You feel anchored to the ancient past, and the foundations of the Western world.

A few miles before the marathon point, Liz and Nick wave from the car as they drive by, having first had a leisurely coffee in Athens after the start. They yell, "slow down! You're going too fast!" "I'm trying! I'm only 5 minutes fast." Evidently Rob (Pinnington) is ahead of me... they are trying to get him to slow down.

Somewhere in here, it did warm up. I put on my arm sleeves. I don't recall where, but in one of the small towns along the coast I saw a bank temperature screen that read 33° C. I did the math... 91° F. Wow. It didn't feel that hot. Either it wasn't really, or the sauna training had worked well. Once it got warm, I was taking full advantage of the checkpoint resources. Sponges over arms, head, shirt at every stop. Ice where I could get it, which was most of the checkpoints, in my bottle, in my hat, and down my shirt. The belt helped here, holding the ice in, something I had planned. More water in my bottle than I could possibly want to drink over the roughly two miles between aid stations; I was liberal in squirting myself to stay wet and cool. Also I was now drinking a cup of Coke at every checkpoint. That would be my primary fuel for the rest of the race, but I had started with four gels, taking one per hour, just so I'd have a bit of variety. And I figured at some point I might want some real food as well; I hadn't run longer than 24 hours before on mostly fat.

I hit checkpoint 11, Megara, the marathon point, at 4:15 on the clock (11:15 am). Eight minutes ahead of my "fastest possible" splits, but that was as slow as I could go. Liz and Nick were here; I took my time catching up. They were worried that Rob was going out way too fast; he'd been several minutes ahead of me here. I didn't understand... he was 0 and 3, and we'd agreed that 9ish was smart at Corinth; I was ahead of that...? I re-applied BodyGlide; shortly this would become a serious issue.

|

| A small quarter sandwich – I think the only solid food I ate. |

After Megara the course became more rolling; we actually had a decent climb, so lots of walking. I caught up to Martin Ilott, of the British Team. I recognized his name from race reports, and struck up a conversation. This was his 11th time here; his record was 5 and 5. He said this year would determine whether he came back... if he didn't finish this year, that would be a sign it was time to hang it up. (Alas, I later learned he didn't finish.) We ran together for a bit, then I pulled ahead. With the hills, I was now slowing down to match my "fastest" splits, even a bit slower.

It was now getting quite hot, and I was passing a lot of people. Early, everyone had passed me. But since the marathon point, nobody had; in fact, I believe literally not a single person passed me between there and around mile 70. Everyone was now paying the price for having started too fast. In my opinion, in a race like this, if you don't feel like you're crawling at the beginning, you're going too fast. I never like to bank time – I like to bank energy.

A few more checkpoints, and I see Mark ahead of me. He's not doing well, says he started too fast. In the end his problem will be the same as mine, chafing, but even worse. He says Dave (Krupski) is just ahead. I catch up to Dave, and we chat for a bit. He had gone out with Mike Wardian and Florian Reus (the eventual winner). Dave has plenty of experience, in particular he finished here last year, so it's not for me to question his strategy. But he was also not doing great now. In his case I think it was because he'd already run eight or so races of 100 or more miles this year, and had hardly run since Badwater. Spartathlon, if he finished it, would be a bonus.

We are running a bit faster than my fastest splits; I try extra hard to slow down, and Dave pulls ahead. But the "big hill" heading into Corinth, that the cutoff times assume you will walk, is really almost too shallow a grade to walk. I'm bleeding time the wrong way. This is the first time I realize that perhaps I should have examined the cutoff times more critically, instead of assuming they were reasonable splits for 36 hours – which actually I knew they weren't, as 9:30 at mile 50 is way too fast for that. Anyway from the start to Corinth, it works out that I'm supposed to be gaining no more than about two minutes on the cutoffs per checkpoint, and some of these it's much more than that, as slow as I can go.

As we get near Corinth there's again a big refinery. But the really amazing thing is the Corinth canal, which cuts through the Isthmus of Corinth, separating the Peloponnese peninsula from the Greek mainland. An attempt had been made to cut this passage in the 1st century AD, but it wasn't successfully completed until 1893. It's very deep and sheer, very striking. I have to stop in the middle of the pedestrian bridge and look down.

|

| Yiannis, Liz, and Nick |

The Race, Part II: Corinth to the Mountain

On to the next phase of the race! The industrial areas were behind me; I was on to the mostly rural and agricultural Peloponnese, with olive groves, vineyards, and ancient ruins. Over the next few checkpoints I caught up to several more people I knew. First I think was Dave. He told me that Chris Roman had unfortunately dropped. Indeed, there he was at the next checkpoint, now crewing for Dave. I felt bad for him, but what can you do? I'd see him again at the next few checkpoints, as Dave and I ran close together for a while. Shortly afterwards we passed George (Myers), stopping to stretch. The heat was getting to him. Indeed, over the past few miles it seemed to me to have gotten significantly more hot and humid. I caught back up to Mimi Anderson; she looked tired and hot. Her watch said it was now 35° C... that meant 95° F. Again, not sure I believe it – the forecast high near Corinth was only in the 80s – but it was definitely hot. Somewhere in here I also passed Sung Ho "Bruce" Choi, American, but running for Korea. He was #331, I was #330; as I approached, another runner told me "hey, you're out of order, you need to pass him". Heh. Also in here I passed Lara (Zoeller). She said she was reduced to running the flats and downhills, and walking the uphills – well, that sounds like a good plan to me here, anyway!

In spite of the heat I still felt pretty good; now, I knew the sauna training had paid off, as had the slow start. I met Liz and Nick again in short order at checkpoint 26, Ancient Corinth. As I loaded up with ice, Nick asked why I wasn't sticking ice cubes into my sleeves. Why indeed? Good idea.

After a fast downhill segment, I hit the 100K mark, checkpoint 28, at 10:52 elapsed. Still six minutes ahead of my "fastest" splits. Staying near these splits now means building a cushion of six or seven minutes on the cutoffs every checkpoint, instead of two minutes, prior to Corinth. So, I'm curious to see how that's going to feel. I'd pledged not to push it – it's still way too early to be working hard. But I was starting to think that sub-30 would be really, really nice. An extra benefit of that would be finishing before the worst heat of the day on Saturday.

At this point we turn inland, and begin a long, slow climb of about 1,500 feet over 20 miles, interrupted by a significant bump and a more significant dip. Or maybe the hill is only 1,300 feet over 15 miles, depending on how you look at it. It seems I am done with catching people I know, for quite a while. Who is ahead of me, among the Americans? Andrei, Connie, and Ken, at least; I have not seen Bill (Zdon), Jason (Romero), Chris Benjamin, Ed (Aguilar), or Karl (Schnaitter). I am assuming based on pre-race conversations that of these all but Karl are likely behind me, but I'm not sure. And I'm assuming that Katy (Nagy), Traci (Falbo), Aly (Venti), and Mike (Wardian) are far ahead.

At checkpoint 29 I have my first drop bag. I quickly retrieve my headlamp and spare batteries, and tuck them in my belt; I won't need them for a while yet. I guess I was a bit conservative in putting them here, but for all I knew I could be riding the cutoffs at this point. This is nominally a crew access checkpoint, but I don't see Liz and Nick; either I was too fast for them here, or they are jumping ahead to catch Rob.

As the afternoon wears on and approaches evening, finally it begins to cool somewhat. This should be good... but I am beginning to get tired. I see a group of three people ahead of me that I am only gaining on at a minuscule rate, if at all; this is a new thing.

Finally we reach the big "bump" in the elevation profile, as we approach the village of Halkion. This is most definitely a walking stretch, very steep. Halkion is checkpoint 32, mile 70.2. It's 12:27 elapsed, still five minutes ahead of my splits, but I can tell I am fading. There are goats wandering in the streets. Leaving, it is sunset. Soon I put on my headlamp.

Now I am losing a few minutes per checkpoint on my "fast" splits. Funny, I have run through the night many times... there is a natural loss of energy as daylight disappears and you have to face the reality that you will be running instead of sleeping all night. But I had been taking it easy, or so I thought, and the cooler temperatures should help.

Over one long stretch in here, someone ran slightly behind me with no headlamp, using mine. I wasn't bothered; I had spare batteries. Whether he was just saving his, or had a malfunction, I didn't know. We didn't talk. The funny thing is, I later saw his race report, where he mentioned me by name, noting that I never said a word. (We all have our names on our bibs, front and back.) Not recognizing him as an American or a Brit, I mistakenly assumed he didn't speak English. Or maybe I was just struggling too much at this point to be conversational. Turns out he's Irish. Maybe I just never looked back at him at all?

Ancient Nemea, at mile 76.6, is a major checkpoint (35). I'm now at 13:51, six minutes behind my splits. Liz and Nick and Yiannis are here, ready to help. I tell them I'm throwing in the towel on sub-30. If I keep trying to track the splits for 29:30, I'll blow up. I need to slow down and regroup. I remind myself that really sub-30 was only a dream goal anyway, and as long as I don't fall apart, I should still be able to finish in a decent time. But the chafing is getting really bad. I realized some time ago that putting ice cubes down the front of my shirt caused the melt to run into my shorts, accelerating the chafing, so I stopped doing that. But the shorts have not dried off. I try to leave my hat with Liz until morning – it's been strapped to my belt, but the extra weight and awkwardness is making that chafe as well – but Yiannis points out that rain is expected, and I might want it later. I grudgingly agree.

Karl is sitting here, nursing an issue with a shin muscle. I wish him luck. Also I see Kostis Papadimitriou, the race director. I compliment him on a wonderful race, but mention that I'm fading. Oh, are you continuing, or dropping? Continuing, of course! I have never yet DNFed a race, after 80 marathons and 40 ultras. There has to be a first time for everything, and this would be the one, but so far the thought of dropping has never entered my mind. Indeed, the single most important quality in an ultrarunner is determination to finish, no matter what. I know that I have this, so I am not worried. I am not subject to the slippery slope of rationalizations. At least I never have been. I can't say that it hadn't occurred to me that Spartathlon would test me as never before, though.

Rob had left the checkpoint shortly before I arrived, but I spent some time there, and I was not moving quickly when I left. So, I was not surprised not to catch him. Soon we began the big dip that I mentioned. Normally this would reinvigorate me, but I was in a bad place mentally due to the fade and the chafing, and to make matters worse, suddenly there was a rock in my shoe, under my left little toe. I couldn't take advantage of the downhill. At the next checkpoint I did what I had to do: sat in a chair, to deal with it. I really hate sitting down in a race. Not only is it time not moving, but I use my muscles in unaccustomed ways, and they complain. And it takes extra energy to get moving again. I get my shoe off... there's no rock. It's the corn/callus under my toe, possibly compounded by a blister. Damn Hokas. They put extra pressure on my little toes. I knew I should have gone with the Fastwitch. Too late now. It doesn't feel like there's anything I can drain. I put the shoe back on and get moving.

But I soon realize that I am going to have to do better than this. I can barely run, the way the toe feels. So at the next checkpoint, 37, I again sit down. This time I have to take off my sock as well as my shoe, and this is where I pay a price for choosing Injinjis (toe socks). Rather, I will pay a price putting the sock on again, getting my toes back in. The bottom of your little toe is the most inaccessible spot on your foot, if you've never tried to pop a blister there. I used a safety pin from my bib, and tediously did the best I could, not really seeing what I was doing. As I sat, I saw Karl go by, moving well, good! Then I saw Connie go by. "I thought you were ahead of me!" I must have passed her in a checkpoint. She asks how I'm doing – "I've been better". She's gone. I've done what I can; putting my sock back on, my legs begin to cramp.

This is the low point of my race, though of course I can't know that at the time.

Leaving the checkpoint, now I'm climbing out of the big dip. A 500-foot climb over maybe four miles. Also we are now on rough dirt roads for a ways, the only non-paved stretch of the course other than the mountain. The next few miles are kind of a blur, as I plod slowly, mostly walking, thinking maybe there is some slight improvement in my toe. I realize that I've gotten sucked into a downward spiral: as my time between checkpoints grows, my fuel rate slows. The 50ish-calorie hits of Coke are coming farther apart. So I begin to drink a bit more to compensate.

Finally the grade levels, completing the long climb that began 20 miles ago. In my mind this ends a phase of the race – really the hardest phase of the race; I'm not intimidated by the mountain, which is just a lot of walking – and this is a good thing. I can try to put my troubles behind me and move on (or as Dave Krupski put it in the very first Spartathlon report I read, "flip the script"). It's time for a 1,000-foot drop over the next five miles, preparatory to climbing the mountain. I'm not a super-fast road runner – I can run a sub-3 marathon on a good day, but not much faster – but as ultrarunners go, I have some leg speed to take advantage of the downhills. Also I have trained my quads to be very resilient. These hills are nothing compared to Western States. So in spite of the chafing, the blister, and the tiredness, I'm excited about this stretch. The blister is definitely better now (or maybe I'm just becoming numb to it). The chafing I will have to address, but I can last until the next major checkpoint, I think, where hopefully they can bandage it. And much as I hate to sit, I think perhaps the time in the chairs helped.

I come into Malandreni, checkpoint 40, at mile 86.9, fairly flying. Liz and Nick are surprised to see me moving so well. Rob is just leaving; I've finally caught him. I tell them I'm much better, but I will have to deal with the chafing at Lyrkia. I spend a few minutes here.

|

| Yiannis and Nick waiting in (I think) Malandreni |

Leaving Malandreni, I'm moving faster than I have the entire race. This is optimal downhill, and now it is fully cool, and I'm engaged in night mode. I fly by several people like they are standing still. Eventually I catch Rob, but he is not in a mood to chat; I wish him well and move on. I think he must now be close to as far as he has gotten here before. Somewhere in here I also pass Karl and Connie. At checkpoint 41, I see I averaged 7:58 pace for the segment. I've finally run out of downhill. It's flat to gradually uphill to checkpoint 42, but I am still energized and running quickly.

Liz and Nick surprise me at checkpoint 42 – they have bandages. This means more sitting in a chair, alas, but it's worth it. Liz holds my headlamp as I carefully apply four or five bandages on each side. I think probably they won't last, but for now at least this should give me quite a bit of relief.

Lyrkia (checkpoint 43, mile 92.1) also sits on a bit of a bump in the elevation profile; as I approach, I suddenly must switch from fast running to power hiking. But I'm still energized going through the checkpoint. This is the gateway to the mountain; I've been told it's all walking from here to the top of the mountain. I grab some Coke and get going quickly. Just as I'm leaving I see Nick, who tells me Liz and Yiannis are in the car just ahead, but I don't manage to see them.

Over the next couple of checkpoints, there is some walking, but much of it is an easy grade and I can't help but run it. I'm thoroughly psyched to have gotten my mojo back. Finally around checkpoint 45 the grade becomes quite steep, and it's now power hiking to the mountain base. I'm still passing people at this pace. The bottom of the hill past Malandreni was at 500 feet; we have to gain 2,000 feet just to the mountain base, then another 1,000 feet to the mountain top.

For a while now I've seen lightning in the distance to the south, and I know thunderstorms are due. I hope the mountain weather is not going to be too brutal. I'm now running parallel to and below the highway, which is all lit up. Gradually by switchbacks it gets closer, and I pass under it. The wind is picking up as I get higher. Finally, I reach the mountain base, mile 99.1. I haven't been checking my splits since Ancient Nemea, but looking back at the data as I write this, I see that I was half an hour behind my target splits here, at 19:09, even after all the fast running. I guess I was really moving slowly for a long time.

Liz and Nick are here, eager to help get me ready. I have a drop bag full of warm clothes. I was hoping for some intel on the mountain weather conditions, but nobody knows what it's like up top. Nick says he went up the trail a ways, and it was quite windy. They convince me to bundle up, somewhat against my better judgment. Longsleeve, hat, gloves. Also they convince me to switch headlamp batteries. I agree, though I grudge the time spent.

Finally leaving the checkpoint, I instinctively start to continue up the road. No, I'm told – it's straight up, up the rough trail to the left. I knew this; I'd read it many times. But continuing straight is habit. I wobble a bit as I start up the trail, that looks more like just a vertical wall. I'm asked if I'm OK, and I think not quite believed as I say yes. Also I had to be reminded to take my water bottle on the way out. Maybe I pushed myself a bit too much with all that fast running?

But the trail is fine once I get going. It's slow hiking, no two ways about it, technical, with sheer dropoffs. You have to be careful. It's pretty well lit, and there are photographers at a couple of points. I pass one person early, then see nobody else on the ascent. I've been told parts of this are hands-and-knees, but it never reached that point for me. I was, however, too hot, right from the start, and I never felt any wind or chill.

In relatively short order, I reached the top. All downhill from here! Haha. Yeah, just the small matter of an easy 53 miles to the finish, after running 100. Here I should mention that this mountain, Parthenion, is where Pheidippides is said to have encountered the god Pan on his journey. Pan called him by name, and asked him why the Athenians paid him no attention, in spite of his friendliness to them. They took this message quite seriously on Pheidippides' return, built a temple to Pan, and instituted annual ceremonies and sacrifices.

I did not encounter Pan. But I well believe that a person here could see anything imaginable. As I wondered, not for the first time, about how Pheidippides could possibly have accomplished his feat, I was again baffled. I couldn't imagine that ascent without a headlamp. Tonight, we also had a full moon. Pheidippides did not. How do I know this? Because when he got to Sparta, the Spartans, though sympathetic, by law could not send help during their religious festival of Carneia. "It was the ninth day of the month, and they said they could not take the field until the moon was full."

Yes, we are nominally recreating Pheidippides' epic mission by running the Spartathlon, but it is kind of a joke. Pheidippides did not have paved roads. He didn't have a headlamp. He didn't have a GPS watch. He didn't have a marked course. He didn't have tech fabrics and cushioned running shoes. Most importantly, perhaps, he didn't have aid stations every two miles. His is still a mind-boggling accomplishment. Last year, famed ultrarunner Dean Karnazes attempted to run the course eating just what had been available to Pheidippides: olives, figs, and cured meats. He finished, but had to abandon the diet at some point, and still said it was the hardest thing he'd ever done.

The Race, Part III: The Mountain to Sparta

The rain started just as I left the mountain-top checkpoint, though for now it was just drizzling. As I had feared, the mountain descent was much worse than the ascent. It was steep and technical, with loose scree. With my poor abused toes, just walking down this was quite painful, and that would take intolerably long. But to run it quickly would be to court disaster. I finally settled on a slow, careful trot. I was dumbfounded as immediately, someone went flying by me. I wished I'd had his feet and shoes at that point. Well, at least my legs still felt good.

To add insult to injury, the trail descent was even longer than the ascent. Finally, with immense relief, I saw road ahead. Shortly, I arrived at Sangas Pass, checkpoint 49. There was a woman sitting in a chair with a glazed expression. But as I drank my Coke, she left just ahead of me. I was running well again, and decided to stay with her, as otherwise the road was empty and lonely at 3 am. But she was running better, and gradually left me behind.

The last 50 miles of the course is supposed to be relatively fast, if you have saved energy for it. It's 20 miles of mostly flat over the plains of Tegea, the flattest part of the course, then a big hill, several miles of rolling, and a long, fast downhill 12 or 13 miles to Sparta. So after just a bit more downhill, I was onto the flat section, down to about 2,100 feet of elevation. I might have hoped this would pass quickly, but it did not. The next 40 miles were interminable, as I kept expecting to be farther along than I was whenever I would check the distance. The problem is that flat and isolated is boring. The only thing there was to break up the monotony was the slight chill and rain, and of course the pain in my feet and increasing chafing at every possible fabric / skin surface. The right little toe had now decided to follow suit with the left, and the left big toenail felt like it was sliding around freely. Every 50 feet so or I would adjust the rotation of my belt, trying futilely to minimize the chafing.

Compounding the challenges of fatigue, boredom, and aches and pains was the simple fact that this race is just... big. That's really the only word for it. I've run lots of 100s, and though it's hard to really conceptualize what running 100 miles means except when you are doing it, nonetheless you can conceptualize the course, and the major landmarks and aid stations along the way. Here I was experiencing a kind of overload in my mental representation of the race. I'd already run 100 miles, and though I had the rest of the course in my head... it just kept going, and going, and going. It's not just the extra length. I've come close to that before at 24-hour; this is different. It's the sheer quantity of different features. You're running through different parts of Greece, and this year, through very different weather conditions. It's too many contexts.

The next major checkpoint (52) was Nestani, at mile 106.6. Like so many other villages, it was sitting on a hill, so there was a bit of walking heading in. Here I'd left a drop bag with a fresh pair of Hokas. But there was nothing really wrong with the pair I had on, other than that they sucked, and a new pair of the same wouldn't help that. However, I eagerly dumped all my warm clothes into the bag, stripping back to singlet. Of course, the moment I left the checkpoint, the sky opened up and started pouring.

I hadn't known it then, but Traci Falbo must have been in very bad condition in the medical section at Nestani when I arrived. She'd been ahead of me, and Liz saw her and her husband there when she arrived too late to meet me. Traci is as tough as they come, but her stomach and the mountain descent had done her in. Over her objections, her crew had to pull her here for medical reasons; they were waiting for the ambulance when Liz arrived.

By this point I must have been back into the mindset of thinking of sub-30 as a possibility again, because I remember checking my splits and leaving quickly, when the volunteers had tried to talk me into a chair and a blanket. For a long while now I would be tracking about 30 minutes off my "fastest" splits, which would put me in right at 30 hours if I could hold it. A big "if", but with the carrot there, my motivation was back.

Lots of the next long stretch were dismal, as the rain poured, everything chafed, my feet hurt, and my energy tried to wane. My bandages had fallen off. I think the worst was the roads where you couldn't see well enough in the dark to avoid the deep puddles, or there was no avoiding them; everywhere you stepped was tromping through lots of water.

Several checkpoints later, during one of these running-through-a-river stretches, my Garmin gave me a low battery alert. Really?? My fancy new 920, which was supposed to get 40 hours in ultra-trac mode? I got 22? That was the last straw; everything about the watch was more annoying than my trusty old 310. I was ready to write Garmin a nasty letter. I turned off the GPS, hoping the watch itself would last for a while longer.

Well, nothing for it but to soldier on. But a checkpoint or two later I noticed that the Garmin still claimed to be accumulating mileage. Then I remembered it had accelerometers, and was tracking inertially. I compared to my split charts, and actually it seemed to be tracking quite well. That meant I could still use it to check my pace and progress. Cool!

Checkpoint 57, Zevgolatio, at mile 115.6, was marked as a crew access point, but again I didn't see my crew. I assumed they were dealing with Rob, which was after all only fair; they were really his crew. Somewhere in here, the belt chafing got too be too much, and I draped it over my shoulder like a bandolier. Much better! The groin chafing, sans-bandages, was still an issue, but the cold was helping there. Also in the rain, it was now so wet that it was more lubricated.

An eternity later, I was finally approaching the next major checkpoint, Alea-Tegea, which would also herald the next phase of the race. Here, disaster struck. In a daze, I guess, I'd blown through an intersection, missing the marked turn. I didn't realize it until quite a while later, when I saw a yellow arrow pointing towards me. That wasn't right. The course was marked with yellow arrows. What was that doing there? I still don't know, but eventually I backtracked to the intersection and found my mistake. If the arrow hadn't been there, who knows how much farther off course I'd have gone. But now I made an even worse mistake. Just as I reached the intersection, my crew vehicle drove through it. I yelled out that I'd just gone way off course. In the confusion, my recalibration with the proper direction was disrupted. I followed the car out of the intersection as they headed on to Alea-Tegea, but I hadn't made absolutely certain I was now following the arrow. After going a long way not seeing any course markings, I eventually decided I (and my crew) must still have taken the wrong way out of the intersection, and turned around. It was a long way back. And of course, no, we'd been going the right way after all.

Finally, very angry with myself, I reached Alea-Tegea, mile 121.4. It was not quite dawn, but just light enough for me to be able to dump my headlamp with Liz. Also I dumped my belt, after transferring my runner ID to the pocket on my handheld, and strapping my clip-on shades to the back of my hat (as if I would need them again, ha!).

Leaving, it felt great to be unencumbered, but I was in a foul mood because I was sure I'd just blown any chance I had left at sub-30, for no good reason whatsoever. The Garmin said I'd just added 1.5 miles to my trip, call it 15 minutes. I had been right on the edge; I didn't see how I could make that up.

A couple of miles later, and we were running along the shoulder of the highway to Sparta, where we'd stay for the rest of the race. Cars whizzed by, usually with a shouted "bravo!" out the window. It was time for the long climb, about 800 feet over five miles. I'd been told to just walk this, and I mostly did, but it was a bit frustrating, just on the edge of something you think you should be running. A Japanese runner (of which there were 60 in the race!) passed me, running very slowly. I had heard, and it seemed to be the case, that the Japanese tend to avoid ever walking, instead getting their recovery in time spent at checkpoints. Different strokes.

Here more problems with my pacing plan became apparent. I was supposed to be making up 6-7 minutes of cushion on the cutoffs per checkpoint, but walking is walking, and it's hard to walk 6 minutes faster than the walking pace assumed by the cutoffs on the hills. I appeared to be losing time on my target splits. After I saw that I was 46 minutes behind at one point, or 16 minutes behind 30-hour pace, I stopped paying close attention; I would run what I could run, but sub-30 appeared to be gone.

Finally the long climb was over, and we began about seven miles of rolling hills. I kept thinking I was farther ahead than I was, anticipating the long descent into the Monument checkpoint. But that was still a ways off. Regardless, I was now taking full advantage of the downhills, running them very fast.

In the daylight, I still didn't see Pan, but I did begin to hallucinate a bit. Specifically, road signs and other objects by the side of the road insisted on being perceived as people, runners to pass, bent over in odd postures. Even when I consciously realized one particular kind of sign was always a sign and not a runner, I couldn't help seeing them as runners.

But there were real runners as well, and I was still passing them. Finally I caught up to one who looked familiar. Was that Ken? My tired brain refused to quite make the connection, though we had spent a lot of time talking over the past few days. Indeed it was. I had wondered how he was doing, for quite a while. Either he was doing well, or he'd dropped. Here he was, so he was doing well. He yelled at me to go get that sub-30. I replied that I maybe could have, if I hadn't gone off course. But I was moving much faster than he was at this point, so the conversation didn't last long. Somewhere over this stretch the crew car is parked by the side of the road, and Liz and Nick wave, and say I look good. Well, of course I do. I'm running fast, with plenty of energy in my legs!

Finally I reach the actual long downhill to Monument. This is a huge relief. There's still one more climb, but the rest of the race is now very simple: run downhill fast, walk up a big hill, run downhill fast all the way to Sparta. Now, I can smell the finish.

I'm now passing people left and right. I recognize British runner Debbie Martin-Consani; she's doing great. I pass Paul Ali as I near Monument. Like most runners at this point, he's protected from the rain and cold, with a poncho. I am loving it in just a singlet. Having lived in Vancouver for 10 years, I'm quite comfortable running in the cold and wet, and it's fast conditions. It would be horrible if I weren't moving well, though.

After leaving Monument, it's a 300-foot climb over maybe a mile and a half. It feels steeper. Anyway, I'm happy to walk it and give my lungs, heart, and legs a break. Now, finally, almost 140 miles into the race... I really need that porta-potty. No pre-race porta-potty, nothing for 140 miles; that must be some kind of record. I find a convenient place behind a bush, and lighten my load.

Now, the top of the hill: checkpoint 69, only five more to go, then the finish. It's time to turn it loose! I think I'm supposed to be able to look down into the valley ahead and see Sparta off in the distance, but it's totally fogged in, and I can't see a thing.

After running a little bit, I realize that I no longer have to check my target splits to see how I'm doing. I know how far I am from the finish, and what time it is, and that essentially everything on the way is fast terrain. And... I have about two hours to run something less than 12 miles. !!! Really, I can get a sub-30 by running 10-minute miles, downhill?!!! How did that happen? Something about my target splits based on the cutoffs is clearly messed up in the later part of the race.

Now I am really excited. For the next few checkpoints I run at about 7:30 pace, and don't stop for Coke or water. I'm on a mission. I am still afraid something will go wrong; the elevation profile looks smooth and downhill, but there are always little bumps, and walking even a short stretch will mess up my average pace. Also I'm not entirely sure I trust my brain to do calculations at this point. Indeed, there is one sizable stretch that's slightly uphill. But every time I check, the numbers get better. Now I have to run 12-minute miles to make it. Now 15.

The weather has become truly abysmal, and even the side of the highway is a river, with no way to avoid trudging through it. But nothing can dampen my enthusiasm now. I pass a few last people, trying to get them to come with me for sub-30. They won't make it. But then a few miles from the finish, I pass an Italian who is moving well. We exchange a high-five. As I pass, he's clearly conflicted. "Is there anyone close behind me?" "No!" To me that means I don't have to worry he will try to catch me. Not that that matters much, but a place is a place. (Actually in the end he almost caught me!)

So finally, as I get closer and the grade levels off, and I am clearly going to make it, I allow myself some short breaks. As I enter Sparta, the downhill is done. It's finally sinking in, I am finishing the Spartathlon, and in a very good time. Wow. I reach the last checkpoint, 74, 1.5 miles to go. From this point I am escorted by a teenager on a bike. He lets me know the course ahead, wants to know where I'm from, my running history.

We turn right; that means there's only one turn to go. I don't realize it until later, but now I am running on Lycurgus Street. Lycurgus was the legendary early Spartan lawgiver, who instituted many of the militarily-oriented reforms that made Sparta Sparta. My great-grandfather was Charles Lycurgus Hearn. He hated the name.

Finally my bike pacer points out the final turn ahead, and I let out a cry of joy. I know that after that, it's just 400 meters to King Leonidas and the finish. You finish the Spartathlon when you touch (most people kiss) the foot of the huge statue of Leonidas at the end of the street.Leonidas was not, in fact, the king when Pheidippides arrived in 490 BC. He was the king in 480 BC, when the Persians were back for a second try; he led the famous Spartan 300 at the Battle of Thermopylae. The plaque on the statue reads ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ – "come and take them". This is what Leonidas, vastly outnumbered by the enormous Persian army, replied to Xerxes when ordered to lay down their weapons. The Spartans eventually fell, but not before inflicting severe casualties, and critically delaying the invading army. In the end the Greeks won. Had things gone differently, we would not have Classical Greek philosophy and democracy as part of our cultural history.

We make the turn. Dave Krupski cheers for me as I go by – which means, unfortunately, that he's DNFed. I see there are other Americans with him, but I am not coherent enough to identify them.

Coming down the final quarter mile was unbelievably emotional. I had imagined this so many times, read so many race reports, seen so many photos. Finally, here I was. The city was cheering, pulling me in, sharing in my triumph. As I got closer, a huge crowd of children joined me, all offering high fives. My name was announced.Where is Leonidas? Finally, the view opened, and there he was. I had made it. I sprang up the steps with a huge grin, and kissed his foot. Done!

After I caught my breath, everything happened at once. Liz was there, I was surrounded by photographers, and I was offered a drink of water from the river Evrotas from a chalice. Then, I received my olive wreath. There was some confusion, as it had not quite occurred to me that my hat was in the way. Next, I was given a bag, prepared for me by schoolchildren, with hand-drawn artwork and a ceramic medal with number on it. After more photos, and soaking it in, I was led away to the medical tent, as is every finisher. Vangelis was playing on the loudspeakers. Not Chariots of Fire, but Come to Me, from the album Voices. Later I think I heard something from Rapsodies, rather obscure. I approved.

In the medical tent my shoes were removed, and my feet cleaned. I hated to look. My muscles were checked and massaged; actually they felt fine. I was really in pretty good shape. A handful of kids appeared, wanting my autograph.

I learned that I somehow had finished in 29:35(!), in 28th place. I don't know where those extra 25 minutes came from, when I'd been so sure sub-30 was out of reach. Also Liz says they'd announced me as the third American finisher, and first American man. I was dumbfounded. I guess that would mean Mike Wardian had DNFed.

I saw Traci's crew, and yelled out for information on how she'd done. Turns out she was lying right across from me, and I got the whole story then. She'd just arrived here from the hospital.

As we got into the provided cab to our hotel – a quarter mile away, at the corner of the final turn, obviously not walkable for someone who'd just run 153 miles! – the music had switched to Zorba the Greek. At the celebration that evening in the main square of Sparta, the live band also played Zorba the Greek. As I finish this report it is 12 days later. And in that entire time, NOT ONCE has Zorba the Greek left my head. I wake in the middle of the night, and it is still playing. I know races like this can change you permanently, but this wasn't the kind of change I expected. Well, at least it's not a ringtone.

After a few hours' crash in the hotel room, Liz and I wandered down to the street, found an outdoor seat at a restaurant, and watched the rest of the finishers come in. There was Mimi Anderson! (And yes – she did it. After sleeping for 12 hours, she turned around and ran all the way back. Amazing.) And Connie! And Ed! And yes, Rob! He finally got his revenge on the course. Of the Americans, in the end 9 of 20 starters finished. The first two were Katy, who ran an unbelievable 25:09, beating the course record by nearly two hours, and placing 4th overall; and Aly, who also managed to beat the old course record. Incredible. If I thought my sub-30 was an accomplishment, I need look no further to regain some humility. But it turns out I had almost caught Szilvia Lubics, the former women's record holder.

The next day we had a big luncheon with the mayor of Sparta, and were given individualized gift bags, with wine, olive soap, and other local products, and a DVD with our personal finish photos. Then, we were bused back to Athens. Or would have been – instead, Nick and Yiannis offered us a ride in their car, as Rob chose to ride the bus. This made for a much more pleasant trip, with great conversation, and none of the bus mishaps the others endured. We stopped for a break at a little cafe on the Corinth canal; a large Greek wedding was going on on the opposite side. Here we also watched a very unusual bridge in operation. When a boat approached, the bridge descended under the water to make room, then rose up again.

On Monday, we saw some sights in Athens, then attended the gala awards celebration dinner.

I finished in 29:35:12, 28th place overall, and 3rd place for 50 and over, of which I'm particularly proud. (Actually I was two weeks shy of turning 50, but in Europe it seems you're listed by the age you will turn that year.)

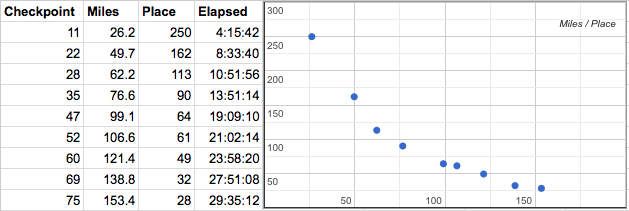

My strategy of starting slow and trying to minimize the fade paid off well. Here's a graph of my race position at each of the timing mats; once past the marathon mark, I passed people throughout the race. Everyone that finished ahead of me was at least half an hour faster to Corinth. My segment splits to Corinth / Mountain Top / Sparta were about 8:35 / 11:10 / 9:50. Still not exactly negative splits, but about as close as you can come at Spartathlon, I think.I love it when a plan comes together!

Overall there were 374 starters and 174 finishers, for a finish rate of 46.5%. That's on the high side of the historical average, which is about a third, though not as high as last year, when over half finished. The cold rain on the second day probably made for faster conditions than heat, though it was hotter than forecast on the first day, and no doubt the dramatically variable weather conditions were challenging for many. Overall I think the finish percentage is trending higher in recent years (with exceptions for particularly hot years), because the level of ultrarunning is rising worldwide, and the entrants are on average at a higher level. This year in particular, the introduction of auto-qualifiers must have made a difference. And for next year, the general qualification standards are being tightened.

Here are all the American finishers (9 / 20 starters):

25:07:12 Katalin Nagy

26:50:51 Alyson Venti

29:35:12 Bob Hearn

30:58:54 Ken Zemach

31:44:46 Andrei Nana

32:22:47 Karl Schnaitter

34:06:14 Lara Zoeller

35:10:03 Connie Gardner

35:40:19 Eduardo Enrique Aguilar

Finally here is a link to my RunningAhead race entry, with all of the checkpoint splits, and here is a link to my pacing spreadsheet.